The Relationship Between Brain Connectivity and New Learnt Skills Based on Cognitive Function Across Different Groups

Ferhia Ibro, Akshaya Ganji, Aamuktha Yalamanchil

Abstract:

Background: Currently, at least two-thirds of the world’s youth are unable to obtain and develop basic skills, and even individuals in high-income countries, a quarter of young people, lack basic skills1. Therefore, it’s imperative to understand how to build and maintain them to set our growing generation up for success.

Objectives: The purpose of this paper is to examine how prevalent the effect of developing skills are within a developing brain in efforts to implement interventions to aid our youth. And so, this leads to the question of how does brain connectivity change when learning a new skill across different age groups. The hypothesis posits that if one learns a new skill over a period of 7 weeks, then their brain connectivity function increases.

Methods: Fifty individuals aged 14 and above voluntarily participated in the study, selected based on their willingness and availability. A Likert-scale survey assessed the perceived effects of learning new skills on cognitive function and behaviour, with pre-study surveys collecting demographic data and current cognitive abilities. The main survey included questions on engagement, problem-solving, memory, focus, creativity, confidence, and continuous learning, administered at 2, 4, and 7 weeks. Informed consent was obtained, and the survey was conducted anonymously via Google Forms, with responses securely stored. Data analysis aimed to explore correlations between learning new skills and changes in cognitive functions, using literature analysis and descriptive statistics to understand the relationship between cognitive function and brain connectivity.

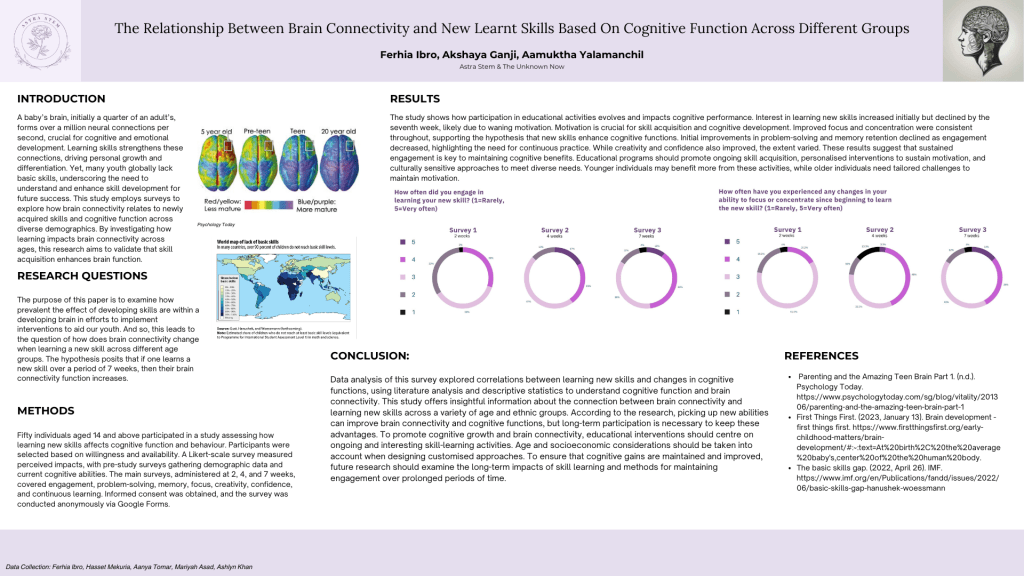

Results: The study shows how participation in educational activities evolves and impacts cognitive performance. Interest in learning new skills increased initially but declined by the seventh week, likely due to waning motivation. Motivation is crucial for skill acquisition and cognitive development. Improved focus and concentration were consistent throughout, supporting the hypothesis that new skills enhance cognitive functions. Initial improvements in problem-solving and memory retention declined as engagement decreased, highlighting the need for continuous practice. While creativity and confidence also improved, the extent varied. These results suggest that sustained engagement is key to maintaining cognitive benefits. Educational programs should promote ongoing skill acquisition, personalised interventions to sustain motivation, and culturally sensitive approaches to meet diverse needs. Younger individuals may benefit more from these activities, while older individuals need tailored challenges to maintain motivation.

Conclusions: This study offers insightful information about the connection between brain connectivity and learning new skills across a variety of age and ethnic groups. According to the research, picking up new abilities can improve brain connectivity and cognitive functions, but long-term participation is necessary to keep these advantages. To promote cognitive growth and brain connectivity, educational interventions should centre on ongoing and interesting skill-learning activities. Age and socioeconomic considerations should be taken into account when designing customised approaches. To ensure that cognitive gains are maintained and improved, future research should examine the long-term impacts of skill learning and methods for maintaining engagement over prolonged periods of time.

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Youth, Neuroscience, Learning Of Skills, Cognitive Function, Neuroscience

Introduction:

A baby’s brain is initially a quarter of an adult brain, producing more than a million neural connections each second2. These neuronal connections are what drives one’s cognitive and emotional growth. Moreover, it’s through the learning of certain skills that fosters these connections and evolve, spurring innovation and growth; and whether that’s done through physical attributes or behavioural characteristics is what ultimately sets us apart from one another. Within this world, certain skills determine your outcome. Currently, at least two-thirds of the world’s youth are unable to obtain and develop basic skills, and even individuals in high-income countries, a quarter of young people, lack basic skills1. Therefore, it’s imperative to understand how to build and maintain them to set our growing generation up for success. However, the question lies in how these skills relate to the brain in efforts to produce the most effective results. This research paper then aims to use surveys to understand the relationships between brain connectivity and newly learned skills based on cognitive function across different ethnic groups. The purpose of this paper is to examine how prevalent the effect of developing skills are within a developing brain in efforts to implement interventions to aid our youth. And so, this leads to the question of how does brain connectivity change when learning a new skill across different age groups. The hypothesis posits that if one learns a new skill over 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 7 weeks, then their brain connectivity function increases.

Methods:

Participants

50 individuals, aged 14 and above, were recruited to participate in the study. Participants were selected based on their willingness to voluntarily participate and their availability to complete the survey during a designated time period.

Survey Instrument:

A Likert-scale survey was developed to assess the perceived effects of learning new skills on various aspects of cognitive function and behaviour. A pre-study survey was administered to determine demographic factors, as well as current cognitive abilities. The 3 main surveys consisted of eight questions covering domains such as engagement in learning new skills, problem-solving skills, memory, focus, creativity, confidence in skill acquisition, and the importance of continuous learning. These questions were administered in 3 different intervals (after 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 7 weeks) to evaluate cognitive function within each respective period.

Administration Procedure:

Prior to survey administration, informed consent was obtained from each participant. The survey was administered electronically using Google Forms. Participants were provided with a unique survey link and instructions for completing the survey during the time period. The survey was completed anonymously, and participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses.

Data Collection:

Participants completed the Likert-scale survey, responding to each question using a scale tailored to the perceived effects of learning new skills. The scale varied according to the question, receiving responses on a range that reflected different levels of agreement, frequency, or impact. The survey responses were automatically recorded and stored securely on the survey platform for subsequent analysis.

Our survey aims to explore potential correlations between learning new skills and changes in cognitive functions and abilities. Through this investigation, we seek to examine various aspects of cognitive function, including memory, mental clarity, processing speed, problem-solving skills, and attention. By analysing the survey responses through our literature analysis and descriptive statistics, we aim to better understand the relationship between cognitive function and brain connectivity.

Pre-study survey results:

Through the pre-study survey, demographic factors such as age, gender, and race were determined. it was determined that 88% of participants are between 14-18 years old, whereas 12% are above 18 years old. In terms of gender, 28% are male, 70% are female, and 2% are non-binary. As for race, 40% are Asian or Asian Canadian, 48% are white or Caucasian, 6% are black or African Canadian, and the remaining 6% are Hispanic or Latino/a. Participants were also asked to focus on one of three categories of skills to focus on in the 7 week period given, those categories being: Cognitive skills, social/mental skills, and motor (gross/fine) skills. Three cognitive based questions were asked:

1. A scale of 1-5, how confident are you in your current cognitive abilities (1 = not confident, 5 = very confident)

2. On a scale of 1-5, how often do you participate in activities that challenge your cognitive skills? (1 = not often, 5 = very often)

3. On a scale of 1-5, how would you rate your current level of mental clarity? (1 = low, 5 = high)

For question 1, 3 types of responses were recorded in Likert-scale manner: 3, 4, and 5. 26% of participants chose 3, 56% of participants chose 4, and the remaining 16% of participants chose 5. These results indicated that participants were moderately–extremely confident in their current cognitive abilities. For question 2, the results were more widespread–2% of participants chose 1, 14% of participants chose 2, 32% of participants chose 3, 36% of participants chose 4, and 16% of participants chose 5. For question 3, in regards to current levels of mental clarity, no participants chose 1, 6% of participants chose 2, 46% of participants chose 3, 38% of participants chose 4, and 10% of participants chose 5.

Results from 3 surveys:

In the 3 surveys conducted in intervals of 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 7 weeks, results varied. In the first question: How often did you engage in learning your new activity? 1-rarely, 5-very often it was evident that there was an increase in 5’s by the 4th week compared to the 2nd week, however by the 7th week, the number of 5’s decreased–indicating that as the survey progressed, there was a spike in actively learning the skill, however by the 7th week, the levels of activity decreased. The second question asked: How often have you experienced any changes in your ability to focus or concentrate since beginning to learn the new skill? 1-rarely, 5-very often; in this question, results were consistent, as throughout the study, the level of 5’s increased from 0%, to 3.3%, and then to 14%. The third question asked: How do you feel your problem solving skills have improved since starting to learn your new skill? 1-not at all, 5-extremely, in this question there was a spike in 5’s as seen in the first question, however, there was a decrease by the third survey; There was an increase from the first survey being 0%, to the third survey being 10%. The fourth question was: Do you believe learning this new skill has affected your memory in the past weeks? 1-not at all, 5-extremely, and the number of 5 results for this question increased as time progressed, going from 4%, to 6.7%, to 14%, respectively. There was a similar spike in the fifth question, being: Has your memory gotten better since learning the new skill? 1-not at all, 5-extremely. In the sixth question: Have you noticed any positive changes in your ability to learn or pick up new skills in other areas not relating to the current skill you are learning? 1-not at all, 5-extremely the number of 5’s increased respectively, the number of 4’s increased from the 1st survey to the 2nd, but then remained consistent in the 3rd survey, and as for the number of 1’s, there was an increase in the second survey from 0% to 3.3%, however, a decrease back to 0% in the 3rd survey. In the seventh question: How confident are you in your ability to perform the new skill? 1-not at all, 5-extremely, results were also varied, as the number of 5’s ranged from 2%-6.7%, however, a decrease to 4% was viewed in the 3rd survey–there was, however, a decrease in 1’s as the survey progressed, as the final survey had no 1’s. In the final survey question: How do you think learning the new skill has impacted your creativity? 1-not at all, 5-extremely, there was an increase in 5’s, however, the number stayed similar by the 3rd survey, going from 4%, to 10.3%, then to 10.2%. An increase in 1’s was viewed from the first survey to the second survey, going from 6% to 13.8%, however, a following decrease by the 3rd survey to 4.1%.

Results:

Access to full results linked here.

Analysis of Literature:

Relationship between Skill Adoption and Age Group

There are different avenues within skills. In efforts to strategically categorise them, this paper will express skills within three groups: cognitive, social/mental and motor (gross/fine) skills. In essence, studies have exhibited results that indicate that cognitive abilities, such as learning and thinking, generally begin to decline after the age of 303. Therefore, with age, the ability to develop certain motor skills is ultimately reduced4. This decline is due to decreased volume in certain brain structures such as the hippocampal, frontal and temporal lobe5, later causing episodic and long term memory decline6. Moreover, the natural loss of receptors and neurons produce concentration difficulties. Hence, the information taken in will process slower;recalling will become difficult due to the inability to fully understand it in the first place7.

However, the brain is a growing organ that functions better when it creates new connections and pathways. Therefore, just as the bodies of children aged 5-12 are growing rapidly, their brains are as well; due to this rapid growth, they are in their prime age to develop certain skills8. In addition, results have exhibited that when compared to adults, children express more dynamic GABA-associated inhibitory processing, which quickly adapts to stabilise learning than in adults. This rapid stabilisation of learning in children allows them to learn larger content within the same time period9.

The skills acquired during childhood become deeply rooted in their minds, yielding fruitful outcomes in the future. A study focusing on children observed instances of early superiority in various areas, exploring how their evolving cognitive abilities, ongoing brain development, limited prior knowledge, and natural inclination to explore enhance their learning and reasoning. It emphasised that due to the adaptive nature of human development, infants and children present ample opportunities to apply cognitive abilities and neural structures in various roles, etc10. For instance, due to children’s large number of synapses, the connections between neurons11, a five-year USC study found significant differences between kids who learned to play instruments and those who didn’t. Through the skill adoption of learning a musical instrument, it not only accelerated brain development, but they also found that auditory systems, and maturity levels increased significantly12.

Relationship between Skill Adoption and Various Ethnicities

A key component of human development is skill adaptation, which shapes possibilities for growth and development. However, this investigation becomes more complex when the variance that exists among various ethnic groups is considered. The process by which different ethnic groups absorb new skills is greatly impacted by institutional barriers and socioeconomic differences. Research indicates, for example, that children from communities and households with lower socioeconomic status (SES) develop their academic skills more slowly than their classmates from environments with greater SES 13. The disparity affects their long-term earnings and health results and spans multiple domains, including cognitive development, language acquisition, memory retention, and socioemotional management. Furthermore, resource limitations are a common issue in low-SES schools, which has a negative impact on students’ overall results and academic performance 14. The cycle of low SES in these neighbourhoods is further sustained by the ensuing insufficient education and elevated dropout rates. Furthermore, there are still differences in literacy abilities amongst kids from various socioeconomic backgrounds. Low-SES households are less likely to provide their children with experiences that help them acquire the necessary reading abilities, such as oral language development, phonological awareness, and vocabulary 15. The differences in educational opportunities and skill acquisition caused by socioeconomic status have an impact on how the brain develops. Neuroscience research has demonstrated the significant influence of early experiences and environmental factors, such as access to high-quality education and enrichment programs, on the development of the brain’s structure and function.16 The lack of engaging learning environments for children from low socioeconomic origins can impede the development of brain networks linked to cognitive capabilities like language processing, memory recall, and problem-solving skills.

17 Furthermore, the chronic stressors associated with poverty (such as inadequate access to resources and food insecurity) can negatively impact brain development as well. Chronic stress triggers physiological responses in the brain, including the release of stress hormones like cortisol, which can impair neural connections and affect cognitive functioning over time.18 The observed differences in academic success and cognitive outcomes between children from lower-class homes and their peers from higher socioeconomic strata may be partially explained by these neurobiological alterations. These neurodevelopmental differences are further exacerbated in low-SES neighbourhoods by the lack of access to early intervention programs and resources. It has been demonstrated that early intervention programs, such as excellent preschool instruction and focused support for children who are considered to be at-risk, have a favourable influence on the negative consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage on cognitive performance.

Brain Connectivity and Cognitive Function

Brain connectivity encompasses both structural and functional aspects, which are integral to cognitive function. Structural connectivity delineates the anatomic substrate of neural communication, revealing the physical pathways formed by white matter tracts19; these white matter tracts link cortical and subcortical regions, and serve as conduits for information transfer between brain regions. Structural connectivity between different brain regions remains relatively stable over short periods of time, such as seconds and minutes–however, over long periods of time, spanning hours to days, these structural connections can undergo modifications in response to experiences or learning processes.20 In other words, while the basic framework of the brain’s structural connectivity remains stable in the short term, it has the capacity to adapt and change in response to external stimuli and experiences over longer periods; this phenomenon is referred to as experience-dependent plasticity.21 Functional connectivity characterises the interactions of neural activity across distributed brain networks, revealing the coordinated patterns of activation essential for cognitive operations. Unlike structural connectivity, which deals with the physical connections between brain regions, functional connectivity examines the statistical relationships between their neural activities22, that being correlations or coherence of neural activity between brain regions, indicating the degree to which they work together.

In this study23 a review of controlled cognitive training (CT) trials revealed increases in functional connectivity within cognitive brain networks following CT interventions. The findings suggest that CT induces enhancements in functional connectivity, reflecting adaptive changes in brain network organisation associated with cognitive improvements. This study connects to the topic of synaptic plasticity24, in which the synapses–connections between neurons–strengthen or weaken in response to activity, contributing to learning and memory processes in the brain. Its connection to the study lies in the adaptive changes in synaptic connectivity which may contribute to the cognitive improvements observed post training. Brain connectivity provides the foundation for cognitive function, as cognitive functions are enabled through structural connectivity, and associated with distinct patterns of functional connectivity. Conversely, cognitive activities can influence brain connectivity, as demonstrated through experience-dependent plasticity. This implies that acquiring a new skill within a set timeframe will boost brain connectivity function, which aligns with the relationship between brain connectivity and cognitive enhancement that this study explores.

Discussion:

The findings of the study prove how participation in educational activities changes over time and how it affects cognitive performance. During the second to fourth weeks, participants’ interest in picking up new abilities increased noticeably; however, by the seventh week, this interest had declined. This pattern might be explained by a decline in motivation or difficulties maintaining a new habit over time. Interestingly, studies suggest that motivation plays a crucial role in skill acquisition and cognitive development; thus, the waning engagement might reflect natural fluctuations in motivation and interest over time. Similarly, the consistent increase in participants reporting improvements in focus and concentration throughout the study indicates that learning new skills positively impacted these cognitive functions. This finding supports our hypothesis that learning new skills positively impacts these cognitive functions, as improved focus and concentration suggest more efficient neural processing and communication. For this reason, the initial improvement in problem-solving skills, followed by a slight decrease, suggests that while learning new skills, sustained practice and engagement are necessary to maintain these benefits. Memory retention exhibited a notable trend where improvements were observed initially but then declined as engagement decreased. This aligns with our hypothesis, indicating that active learning and engagement in new skills are critical for maintaining and enhancing memory functions. The decline in memory retention as participants’ engagement decreased highlights the importance of continuous practice and cognitive stimulation to sustain cognitive benefits.While there were positive changes in creativity and confidence, the improvements were not as pronounced as in other cognitive areas. This suggests that while learning new skills can stimulate creative thinking and boost confidence, the extent of these benefits may vary depending on the type of skill and individual differences in engagement and motivation.The results partially support our hypothesis that learning a new skill enhances brain connectivity and cognitive function. While there was a general improvement in cognitive functions such as focus, problem-solving, and memory, the decline in engagement and subsequent cognitive benefits towards the end of the study suggests that continuous practice and sustained engagement are crucial for maintaining these improvements. This finding shows the importance of consistent engagement in cognitive activities to achieve lasting enhancements. In order to optimize cognitive benefits, educational programs should promote ongoing involvement in the acquisition of new skills. The findings have important implications for educational interventions targeted at youth development. To maintain motivation and cognitive benefits, schools and other educational institutions should incorporate regular and varied skill-learning exercises. High levels of engagement can be sustained with the support of personalised interventions that gradually address motivational decline. Moreover, incorporating strategies to maintain long-term commitment to skill development could lead to sustained benefits. Also, younger individuals, due to their rapid brain development, may benefit more significantly from skill-learning activities, while interventions for older individuals might need to focus more on maintaining motivation and providing appropriate challenges. Interventions should be culturally sensitive and inclusive, ensuring that they meet the diverse needs of different demographic groups.

Conclusion:

This study offers insightful information about the connection between brain connectivity and learning new skills across a variety of age and ethnic groups. According to the research, picking up new abilities can improve brain connectivity and cognitive functions, but long-term participation is necessary to keep these advantages. To promote cognitive growth and brain connectivity, educational interventions should centre on ongoing and interesting skill-learning activities. Age and socioeconomic considerations should be taken into account when designing customized approaches. To ensure that cognitive gains are maintained and improved, future research should examine the long-term impacts of skill learning and methods for maintaining engagement over prolonged periods of time.

Acknowledgments:

Data collection: Ferhia Ibro, Hasset Mekuria, Aanya Tomar, Mariyah Asad, Ashlyn Khan

References:

1. The Basic Skills Gap. IMF https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/06/basic-skills-gap-hanushek-woessmann (2022).

2. Brunton, R. 22 Statistics You Need to Know About Childhood Brain Development. ZERO TO THREE https://www.zerotothree.org/resource/distillation/22-statistics-you-need-to-know-about-childhood-brain-development/ (2022).

5. Healthy Aging. Memory and Aging Center https://memory.ucsf.edu/symptoms/healthy-aging.

6. [No title]. https://www.apa.org/topics/aging-older-adults/memory-brain-changes.

7. How aging affects focus. Harvard Health https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/how-aging-affects-focus (2022).

8. Cognitive Development: School-Age. https://www.virtuallabschool.org/school-age/cognitive-development/lesson-2#:~:text=Just%20as%20children’s%20bodies%20grow,ages%20of%205%20and%2012.

9. Why do children learn more quickly than adults? New study offers clues. Brown University https://www.brown.edu/news/2022-11-15/children-learning.

11. Dvoskin, E. Children’s Brains and Learning. https://kids.uconn.edu/2022/05/10/childrens-brains-and-learning/ (2022).

12. Gersema, E. Children’s brains develop faster with music training. USC Today https://news.usc.edu/childrens-brains-develop-faster-with-music-training/ (2016).

14. Website. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-05694-001.

15. Buckingham, J., Wheldall, K. & Beaman-Wheldall, R. Why poor children are more likely to become poor readers: The school years. Aust. J. Edu. Chem. (2013) doi:10.1177/0004944113495500.

17. Read ‘Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation’ at NAP.edu. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/19401/chapter/8 doi:10.17226/19401.

19. Structure and function of complex brain networks. (2013). PubMed Central. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3811098/#:~:text=Structural%20connectivity%20describes%20anatomical%20connections,linking%20cortical%20and%20subcortical%20regions.

20. Brain Plasticity and Behaviour in the Developing Brain. (2011). PubMed Central. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3222570/

21. Editorial: Experience-Dependent Neuroplasticity Across the Lifespan: From Risk to Resilience. (2018). PubMed Central. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6345705/

22. Friston, K. J. (2007). Functional integration. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 471–491). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-012372560-8/50036-x

23. The Effects of Cognitive Training on Brain Network Activity and Connectivity in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases: a Systematic Review. (2020). PubMed Central. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7305076/24. Home. (n.d.). OECD iLibrary. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9789264270695-11-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/9789264270695-11-en#:~:text=Experience%2Ddependent%20plasticity%20represents%20the,dependent%20plasticity%20needs%20to%20occur.imilar by the 3rd survey, going from 4%, to 10.3%, then to 10.2%. An increase in 1’s was viewed from the first survey to the second survey, going from 6% to 13.8%, however, a following decrease by the 3rd survey to 4.1%.